What are decisions all about?

Decisions form the basis of human action. We need arguments to make or explain decisions. Decisions not only affect us, but also other people. That is why decisions are so important.

Decisions are often made in the background, in private or even in secret. That’s fine, but when it comes to other people, transparency is an advantage. Transparency creates trust. Democracy needs trust, just like a doctor or a lawyer.

How would you feel if the decision-making processes of politicians, doctors or lawyers were available, with weightings, arguments (evaluated criteria) and the possible options? And neatly calculated and documented?

Wouldn’t that be extraordinary? And that could apply to many areas of life.

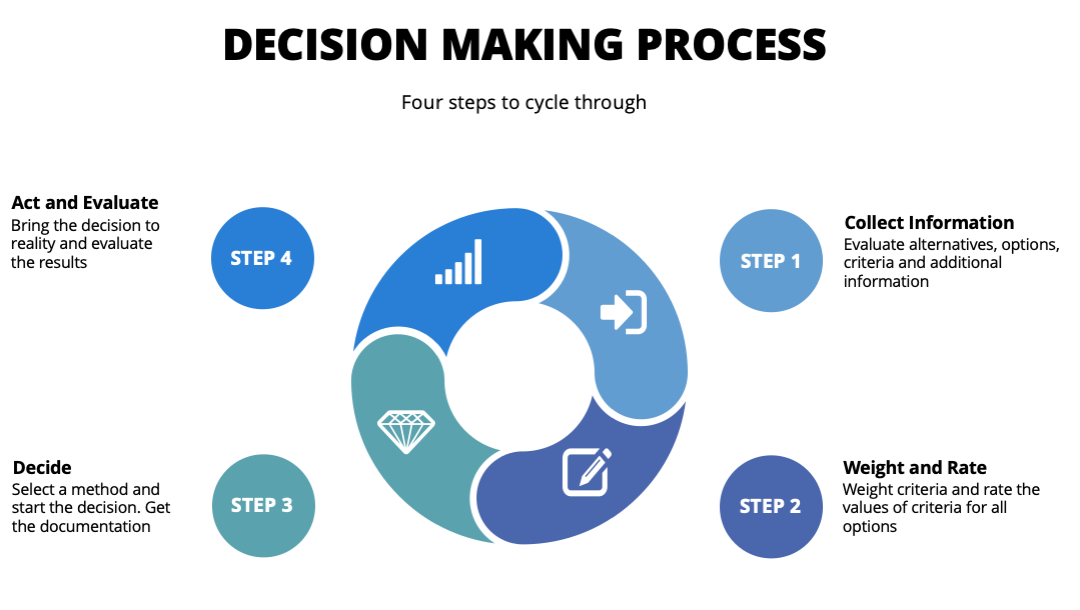

Speaking of life: Life goes on and new options open up and suddenly new evaluation criteria apply. In this case, it is good if we can revisit an “old” decision, add these new factors and review the decision again. In most cases, by the way, the result remains the same.

But how do we make decisions? And what about the famous gut feeling, which is so often different from a technically calculated decision? There is a solution to this.

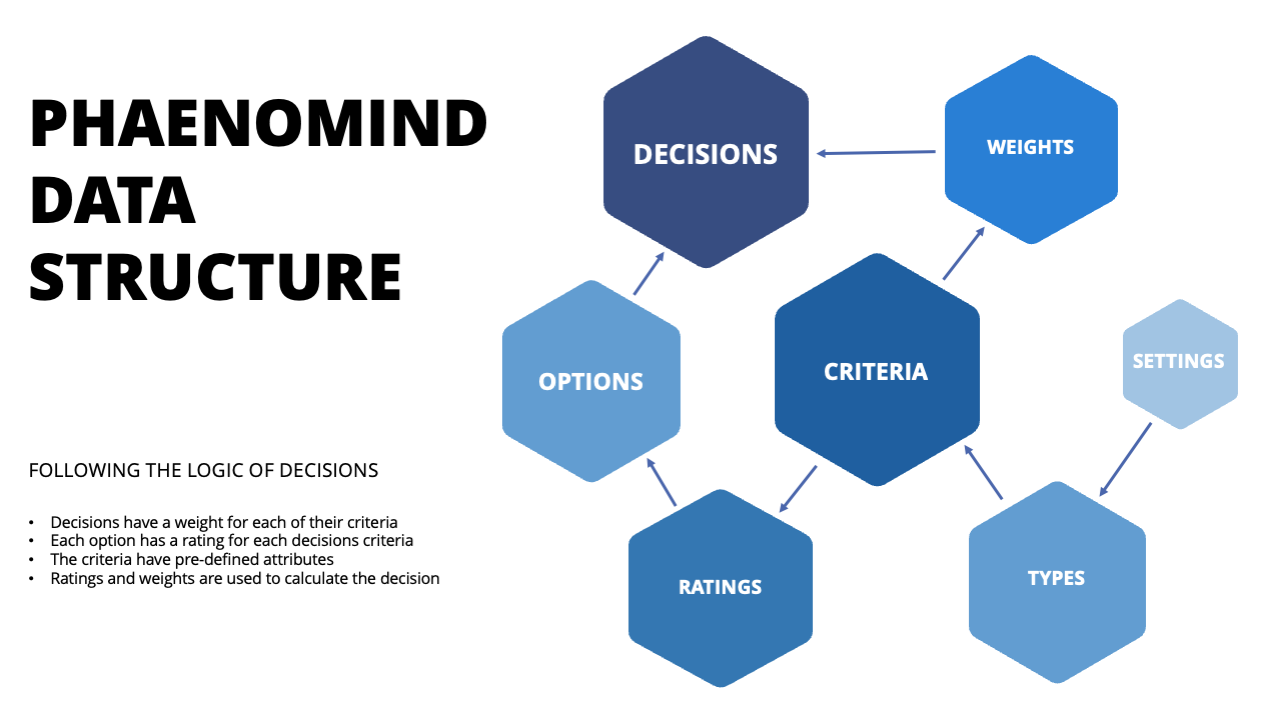

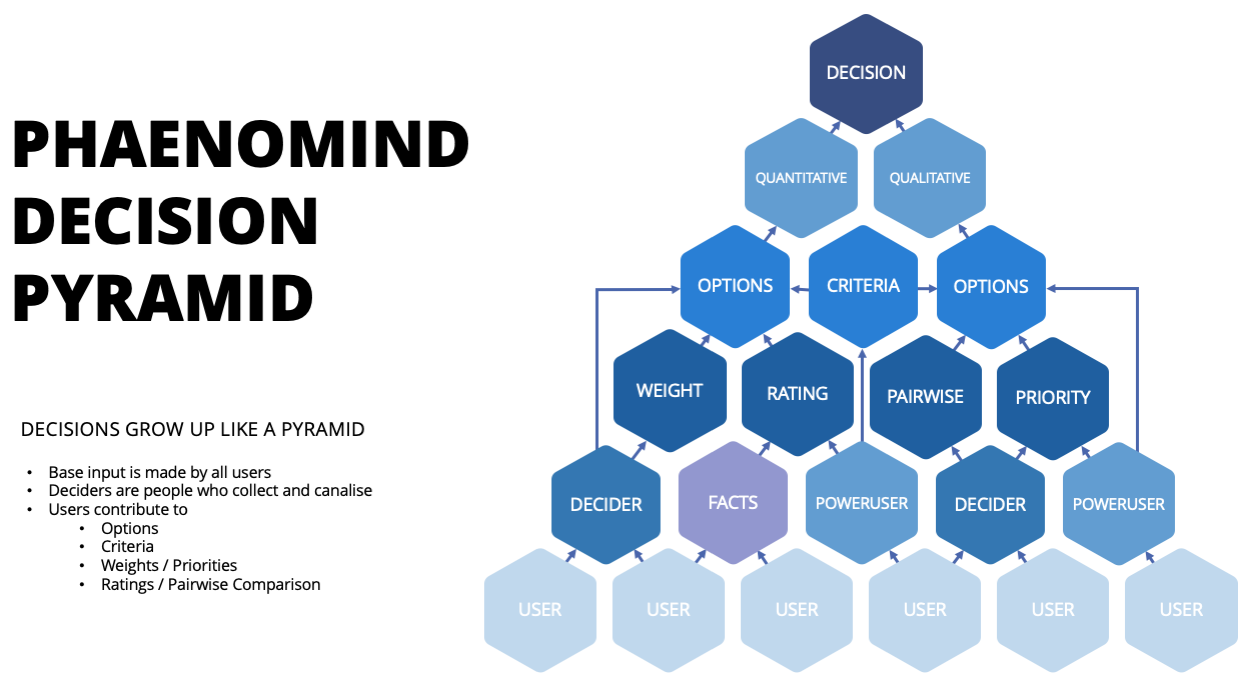

There are many methods for making decisions. Many, in fact. We have focused on two basic methods: The so-called “Utility Analysis” and the so-called “Pairwise Comparison”. The two methods could not be more different.

The Cost Utility Analysis is a purely technical analysis of the available criteria for all alternatives or options. Criteria are determined and filled in for each option. For example, in the case of cars, the fuel consumption or the space of the interior. These can then be standardized so that apples are not compared with pears. And then these criteria can be prioritized, i.e. they are put in order. You can then calculate a value for each option - and the highest value wins, i.e. is the best choice. These criteria of the utility analysis are quantitative values, i.e. numbers that we can specify because they represent a discrete value.

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is completely different: Here, all options are first compared with each other and weighed against each other with regard to one criterion. Does that sound complicated? An example: Three applicants are assessed on the subject of likeability. There is no number that can be used. But a direct comparison is possible: A is much more likeable than B and C is slightly more likeable than B. We carry out these comparisons for all non-measurable criteria. Then we also weigh up the criteria against each other. So likeability is slightly more important than language skills, but specialist knowledge is much more important than likeability.

A result can then be calculated from both evaluations. In most cases, this result corresponds to the gut feeling. It is called a qualitative assessment. And if the “real” gut feeling does not match the result? Then you have done something wrong: you have not included criteria or you have evaluated incorrectly.

So in the end we have two results: One from the quantitative evaluation and one from the qualitative evaluation. These can now be compared and weighted, for example 60% qualitative and 40% quantitative. Then the gut feeling prevails.

It will be interesting if we try out a few things:

- Shifting the two results against each other

- Changing the evaluation of the qualitative criteria

- Changing the prioritization of the quantitative criteria

This allows us to determine when a decision “tips over”, i.e. a different result is calculated. You can learn something from this - but usually it remains with the first calculated result.